Wyatt Kahn

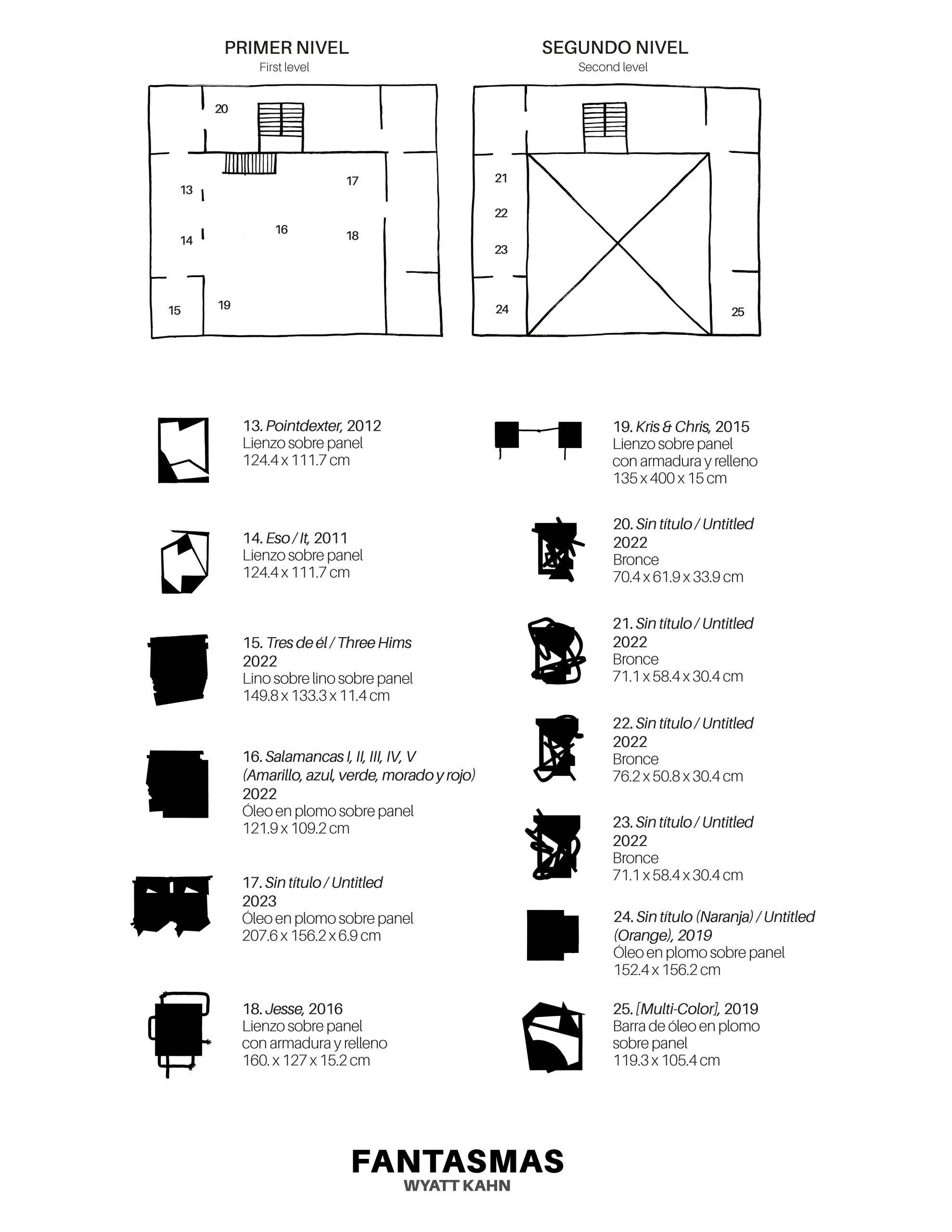

Fantasmas

El ser humano es una suma de capas -a veces contradictorias- que se traslapan: lo que vivimos en el pasado se superpone para construir lo que somos hoy. De vez en cuando emerge -como un fantasma- alguna capa que parecía olvidada.

El Anahuacalli, la última y más compleja obra de Diego Rivera, es reflejo de las capas que lo conformaron, del camino y las contradicciones que tuvo que transitar para llegar a ser lo que fue. Diego evolucionó de la pintura a la esculto-pintura y, finalmente, a la arquitectura. Rechazó las corrientes académicas, experimentó con el cubismo y el funcionalismo, y buscó una expresión de lo que el arte le significaba. El Anahuacalli es resultado de esa búsqueda.

En este espacio el espectador siempre es un elemento activo, como también necesitamos serlo frente a la obra de Wyatt Kahn. De la misma manera en que el cineasta ruso Sergei Eisenstein -admirado por Diego- montaba sus tomas una arriba de otra para lograr un todo, Fantasmas nos invita a reconocer fragmentos traslapados para dar un sentido de totalidad. Jugando con opuestos complementarios, las piezas de Kahn se construyen de atrás para adelante, sugieren profundidad a partir de lo liso, cubren para dejar ver lo que hay debajo.

La obra de Wyatt también transita entre la pintura y la escultura, entre lo plano y lo tridimensional, entre lo figurativo y lo abstracto; se coloca en ese límite, como en una membrana que comunica un lado y el otro. Lo abstracto en Kahn refiere a la manera en que Diego entendía el término: “La teoría abstracta es realista, puesto que reivindica el derecho de la pintura para usar las formas y los colores, las calidades y las profundidades de la misma manera que los músicos usan los sonidos: creando una realidad paralela.” Para Diego era importante defender las formas, las partes, las capas; lo abstracto como algo real, que no tiene forma, pero que existe.

Kahn toma del cotidiano formas universales y reconocibles, que se suman para formar patrones: un abecedario personal desarrollado en casi 20 años de labor artística. De igual manera la colección de arte prehispánico de Diego -y con la que dialoga la de Wyatt- privilegia esas piezas que hablan del día a día de la experiencia humana.

Diego y Wyatt son artistas que parten de lo cotidiano para moverse en estos no-lugares, en estos espacios intermedios, desde donde, lejos de levantar muros, construyen puentes y más capas. En un mundo de extremos, Diego y Wyatt proponen visiones móviles, optimistas.

Dentro de esta casa llena de ídolos viven los fantasmas de todas esas capas que conforman lo que Diego fue. Hoy también conviven con las apariciones que Wyatt trae a flote, que emergen aquí, dentro de esta pirámide contemporánea que les da la bienvenida.

Wyatt Kahn

Ghosts

Human beings are an accumulation of overlapping, often contradictory layers: the events of our past are superimposed to construct the self of today. Sometimes, a layer we had thought forgotten emerges – like a ghost.

The Anahuacalli, the final and most complex work in Diego Rivera’s oeuvre, is a reflection of the layers that make it up: of the path it took and the contradictions it traversed in order to become what it became. Diego’s evolution took him from painting to sculpture-painting and finally to architecture. He rejected the academic currents of his day, experimented with cubism and functionalism, and sought to find an expression of what art meant to him. The Anahuacalli is the result of that search.

In this space the spectator always takes an active position, which is also what is required of us when faced with the work of Wyatt Kahn. In the same way that the Russian filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein – much admired by Diego – assembled images one on top of the other in order to create a whole, Ghosts invites us to recognize overlapping fragments which impart a sense of totality. Playing with complimentary opposites, Kahn’s pieces are constructed from back to front: they suggest depth by way of the flat; they cloak in order to make visible what lies beneath.

Wyatt’s work similarly moves between painting and sculpture, between flat and three dimensional, between figurative and abstract: it places itself on the boundary, as if upon a membrane which communicates between one side and the other. The abstract element in Kahn’s work reflects the way that Diego understood the term: “Abstract theory is realist, given that it vindicates the right of painting to use shape, color, quality and depth in the same way that musicians use sound: in order to create a parallel reality.” It was important for Diego to defend shapes, elements, layers – the abstract as something real, which doesn’t have a form but exists nevertheless.

Kahn lifts universally recognizable shapes from everyday life and compiles them to form patterns: a personal alphabet developed over his almost 20 years of artistic practice. He favors pieces which speak to the day-to-day texture of the human experience – much like Diego’s collection of preHispanic art, which is in conversation with Wyatt’s pieces.

Diego and Wyatt are artists who take everyday life as a starting point from which to move in these non-spaces – the in-between places – from which they construct bridges and more layers instead of raising walls. In a world of extremes, Diego and Wyatt propose mobile, optimistic visions.

The ghosts of all of the layers that made up Diego live inside this house filled with idols. Today they coexist with the apparitions that Wyatt brings with him, which emerge within this contemporary pyramid to which we bid them welcome.